A benefit greater yet

How does endogenising the population affect the marginal technological externalities of one additional birth?

Previously, this blog has estimated optimal population subsidies, finding them to be $210,000 under a 7% discount rate, or $1,200,000 under a 5% discount rate. However, this model took fertility as entirely exogenous: surely an unreasonable assumption. What if it is endogenised?

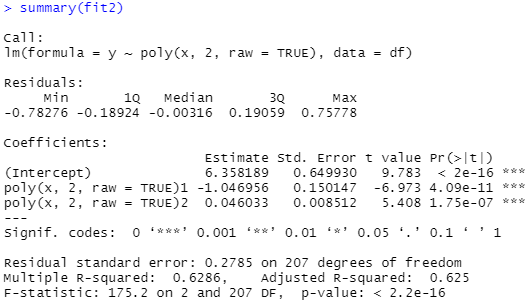

Figure 1 shows that taking natural logs of both gives a clear correlation between the two. However, especially interesting is the regression results:

As can be seen above, adding a cubic term to the regression substantially reduces the p-values of all coefficients without any substantial improvement in the goodness of fit, so can be safely rejected. Interestingly, however, the quadratic term is positive, has a slightly improved goodness of fit and still has excellent p-values. This finding is not original - a tick-shaped curve rather than a linear decline fits the data better if HDI instead of income is used, and those on very high incomes now have more children than the middle class. This gives an income that results in a minimum fertility rate of $86,838, with global incomes increasing beyond that level resulting in a net increase in population.

To ease with computing the model, this blog will assume that society will face a continuous decline equivalent to the TFR every 40-year period, rather than using generations, as non-constant generational lengths over time would interfere with the by-year component of the previous model for optimal population subsidies.

This assumption is likely responsible for the predictions of a decline over the next eighty years in population without subsidies, despite almost all analysis predicting an increase, as it is the case that the TFR of everyone who is either at or below childbearing age is below 2, but due to only the latter half of this group actually breeding the effects differ. To the extent that the actual population is higher, this model will have undervalued the marginal - as this blog has previously showed that the marginal benefit in the exogenous case is linear to the population - meaning that this will not exaggerate the benefit.

As in this model, income eventually grows at a faster rate than any discount rate, the benefits of one additional person, considered over an infinite timeframe, are necessarily infinite when faced with any constant discount rate. Philosophical systems that favour a zero discount rate, such as longtermism, should thus view the optimal subsidy as one as high as possible. However, to achieve a finite result, what if we cut off consideration of benefits beyond a given date?

Table 1: Marginal benefit of a birth by date excluded beyond and discount rate

2.5% was selected as a discount rate as this is roughly equivalent to a pure time preference of zero under prevailing global economic and population growth levels. Interestingly, Table 1 suggests that the previous estimate of the benefits was slightly too high under a 5% discount rate, but considerably too low under a 7% discount rate. In the most extreme case modelled, the present value of all births was 33 times greater than global production last year: even in the least extreme case, it was still equal in value to 55% of the world’s production. Importantly, these benefits all increase rapidly with an increased gain in population:

The steep slope of the 2.5% graph in particular shows that the benefits are even greater than Table 1 implies, as a subsidy of the level of Table 1 would increase the population by a non-infinitesimal amount, resulting in the new marginal benefit being substantially higher than the previous.

In conclusion, a longtermist should regard the marginal benefit as infinite and a non-longtermist should regard the marginal benefit as effectively infinite, in the latter case due to the inability of governments to spend much above half of their national income. The implications of this for government spending are noteworthy - non-research health spending in particular seems likely to have gains far below this - and suggests that the reduction in the birth rate that housebuilding restrictions may cause might even be their primary negative effect. These effects, and other potential optimization opportunities these estimates present, will be explored in a future post.