Open borders has been advocated as a policy that could rectify the gigantic inequities of segregation by place of birth, consigning billions to destitution and death. However, critics come with two principal lines of attack: either that moving costs are so large as to render the policy incapable of helping those that it should, or that moving costs are so low as to completely overwhelm the public services of destination countries. This post aims to show that the first is true in the short-run, but the second in the long-run, meaning that the case for open borders is stronger than would be the case in a world where the claims of one set of critics were entirely unfounded.

In order to assess moving costs, we can investigate existing examples of open borders. Puerto Rico has a per-capita income just over half that of the United States, representing a difference of 0.669 utils in quality, and presently has an annual net emigration rate to the US of 2.8%. Assuming emigration as a percentage of population between two countries is directly proportional to the utility difference between them, this implies emigration to the UK in the first year alone of 466 million, or to the US of 775 million, representing 700% and 230% of population respectively - manifestly unreasonable, especially given that only 750 million people profess a desire to emigrate in the world.

Why does this model give such absurd results? One possible reason is that it fails to take into account diaspora mechanics, as a larger diaspora could reduce the subjective costs of migration by reducing the extent to which individuals need to leave their culture, friends and family in order to exploit economic benefits. This would mean that very large migrant flows would only occur slowly initially, but would gradually build up over time before reaching extremely high levels. This point can be illustrated with Puerto Rico, which has had open borders with the mainland United States since annexation in 1898, but migration was initially extremely slow: only 2000 over the entire first decade. However, this peaked at 450,000 five decades later - 20% of the entire population!

Due to the time spent to create the model, for the purposes of this post, this blog will be using a simple model where the assumptions made are as follows:

Immigrants transfer half of their low productivity to their destination country.

Immigrant children are economically identical to natives.

Immigrants have 40 years of life remaining upon entering the destination country, so 2.5% of the per-capita income drop from 1. is undone every year.

Immigration is directly proportional to the product of the diaspora and the utility difference.

All countries grow at the same rate.

Population growth is zero, and equal worldwide.

Every country in the world currently has a diaspora of 10000 in the UK/US.

Emigration does not affect the GDP per capita of the countries of origin of the emigrants.

Diaspora members are either immortal or children of emigrants form as attractive a diaspora to prospective immigrants as the emigrants themselves did.

Immigrants are as productive as the median member of their society.

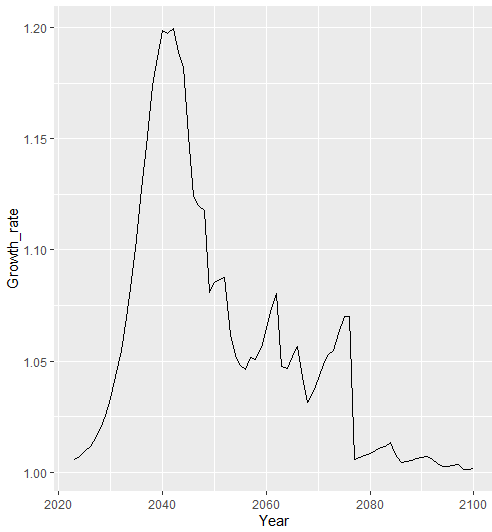

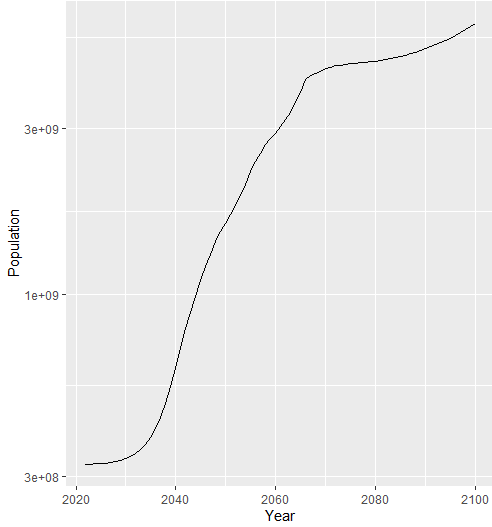

Of these, 5., 6. and 8. seem particularly egregious, and this blog aims to revise the model to account for these in the future, and ideally generalize some other simplifications as well. However, if these are assumed, then the implied trajectories of the UK and US population are:

The population growth levels noted above are very high, peaking at 20% in the UK case and 14% in the US case. However, they are far lower than the 700% and 230% computed earlier, and importantly build up over a 20 year rather than 1 year period, allowing the economy to adapt to an environment of extremely rapid population growth. Additionally, applying the equations of one prominent paper related to institutional damage from immigration to the UK context gives a 5% lower bound for the UK (95% confidence optimal level higher than this) of 34% annual population growth before the marginal impact of additional immigration is negative, meaning that the level of immigration under open borders would, even under the conservative assumptions of the paper, be lower than the optimal level.

(For those wondering if the UK could sustain a population of 4 billion: the UK has a land area of 243,610km^2, and the highest population density area is Islington with a population density of 16000 people per kilometre squared, resulting in a maximum population of 3.9 billion if the entire UK were to merge as such. Building taller buildings would of course allow this density to increase beyond this, rendering UK populations of this magnitude possible, if perhaps suboptimally high. In the US case a population of 6 billion is of course possible, given the 9.834 million km^2 land area it possesses.)

This means that open borders would achieve population growth levels at not much below the optimal rate, and thus would succeed in lifting billions from extreme poverty without killing the institutional geese that lay the golden eggs in the destination country, even if only a single country had open borders.