Open borders has been previously modelled on this blog, with the conclusion reached that the UK population would reach 4 billion by 2100. However, a movement this large from developing to developed countries could potentially boost global carbon emissions - which, if the impact of climate change is sufficiently negative and this effect is large enough, could even cause open borders to reduce global wealth in the long run, although to no greater extent than economic development generally.

Once the statistics are investigated further, it is in fact non-obvious that open borders increases emissions. British emissions per capita stand at only 65.5% of China’s, despite the former’s GDP per capita being 3.8 times higher. India’s emissions per capita are 36.5% of Britain’s while Africa’s stand only at 20.4%. However, these emissions amounts will both rise in the short term and stay positive for decades, while Britain and most other developed countries have pledged net zero emissions by 2050. If we assume countries will implement their emissions pledges, how would the climate fare under open borders?

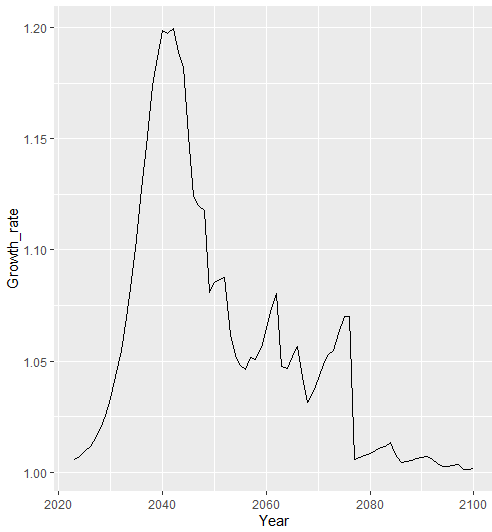

The previous model of immigration used on this blog used the population and GDP per capita of every country in the world, which will not be possible here due to requiring a corresponding model of every country’s climate policy. Instead, the four groups of countries used by the World Bank - low income, lower middle income, upper middle income and high income - have each been assumed to follow the same climate policy, and have the same income. This model does give noticeably different results from the more complex model used previously, predicting a population in 2100 of 4.3 billion for the UK, rather than the 3.7 billion previously forecasted. The comparison between the population growth levels can be seen below.

A model for pollution also requires estimates of the emissions paths of countries today. The UK, along with most of the rest of the developed world, has pledged net zero emissions by 2050, and a linear decline from present emissions to this level will be taken to be the path of emissions under climate change. China has a net zero target of 2060, India of 2070 and Africa will be optimistically assumed to reach net zero in 2080, with countries emissions assumed to all peak 30 years before the net zero date, increasing linearly to said maximum and decreasing linearly afterwards. These environmental policies will also be assumed to be followed by countries of similar income levels.

This model would imply a fall in total global emissions over the next 78 years from 951GtCO2e to 899 GtCO2e, which at 5.4% is not insubstantial if climate change threatens to cause a 25% reduction in global GDP, as some models suggest. However, to cast this as necessarily a reduction, as although emissions in India or Africa may be comparable to or higher than the UK in the long run, these emissions only happen in the future, while UK emissions happen today. Because income increases over time, we should discount costs that occur in the future as the marginal cost of suffering any given pecuniary loss decreases with rising income, due to diminishing marginal returns. The correct rate to discount at in climate economics is a topic of considerable controversy: Stern and Nordhaus predominately derived their differing results from using 1.4% and 5% discount rates respectively. If a 5% discount rate on the social cost of a tonne of carbon is used here, open borders represents a present value decrease in carbon emissions of 0.37%, which given the already exceedingly low present costs of climate change under such a model is negligible: if a 1.4% discount rate is used, it represents a decrease in the present value of carbon emissions by 1.0%.

The assumption that all countries will follow their net zero pledges is likely egregious for calculating the absolute emissions change, but may have limited impact on overall prediction of an emissions reduction. This is because countries emissions are likely non-independent, both because technology invented by one country to lessen the trade-off between production and pollution is in the long-run non-excludable but also because the exact cost of reducing emissions is currently uncertain but will be strongly correlated across societies, meaning that to the extent that the developed world achieves net zero earlier or later than its targets the developing world is likely to follow suit.

It is important to note that due to the large differences between this and the also heavily flawed more detailed model these results are not sufficient to conclude with any certainty that open borders would reduce total emissions, and to the extent that that is concluded it is far from the most effective environmental policy on the margin. Rather, this does hint that the effects of open borders on the environment are mildly negative at worst and the modulus of the effect is small, so environmental considerations should hold little sway on immigration policy - and fears that a more mobile world will be a much warmer one can be safely laid to rest.