Tsunami invariant

How does inclusion of remittances, endogenous capital stocks and immigrant effects on productivity affect the path of the population under open borders?

Previously, this blog has modelled immigration were a single country to pursue a policy of open borders. However, this made numerous simplifying assumptions such as zero economic growth, zero population growth and no effect on the incomes of countries of emigrants. These will be generalized in this post to provide a more accurate estimate for the path of migration under such a policy.

A summary of the modifications is as follows, with justification below. Assumptions not mentioned should be presumed to have persisted.

Remittances are equal to 15% of income multiplied by one minus the proportion of the extant population of the country, and children send no remittances.

Economic growth follows the Solow model under an optimal investment schedule, with capital entirely immobile as immigrants transfer between countries. Capital and productivity differences are equally responsible (as Solow originally found) for differences in income between countries.

Immigrants affect total productivity in the countries they move to, with the exact change varied below.

Effective diasporas halve per generation at steady-state.

Remittances are assumed to decline in proportion to the proportion to the population from a maximum level of 15% as individuals do not send payments to random recipients within their origin country, but to their family: and if the individuals migrating are representative of the country of whence they originate, the average proportion of family still in the origin country will equal the distribution of the extant population of said country, and remittance flows will be assumed to follow accordingly.

The Solow model, a simple relation between income, productivity, labour and capital, will be used in this post. The capital stock will be conservatively assumed to be entirely immobile between countries, exaggerating the short-run income changes that a reallocation of labour relative to capital would result in. Decidedly unconservatively total factor productivity will be assumed to hold constant between countries over time, meaning no catch-up growth is occurring.

The practical implication of these changes is that the previous assumption that immigrants would transfer half of their low productivity can be disposed of, with instead immigration now being prevented from being an instant surge by the negative shock to capital per worker in the rich world and the positive shock to capital per worker in the developing world, and the remittances which flow back to the developing world boosting the capital stock in the short-run further. The productivity assumption is varied to test if the case for open borders is highly sensitive to it.

As previously, the population will be kept constant over time, due to properly modelling of it likely requiring a compartmental model of age as younger individuals are more likely to move and more likely to have children.

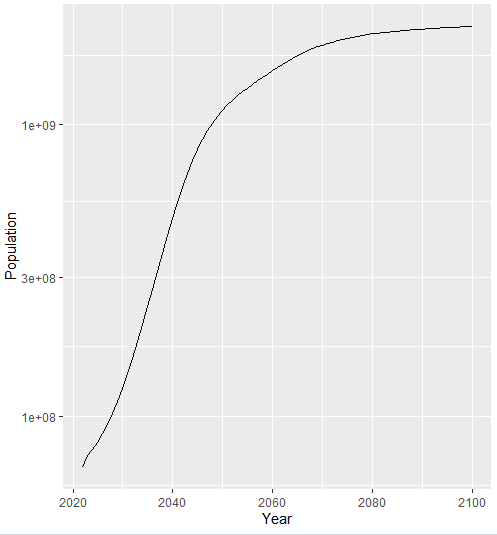

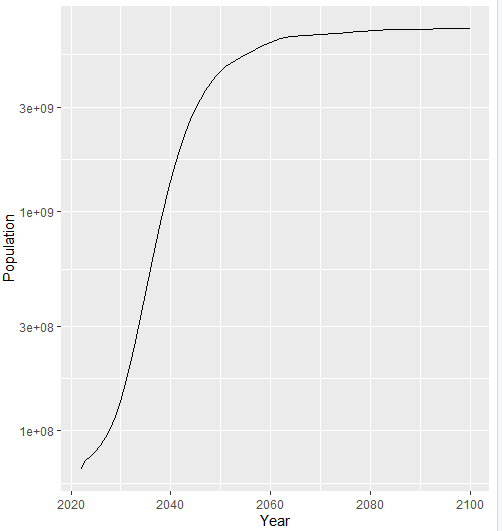

The results are as follows:

Interestingly, these results imply the case for open borders is robust to even substantial negative impacts on productivity - anybody maintaining that the immigration-TFP elasticity was -3 would need to claim that income per capita would be in excess 64% higher than today (rather than lower, as would likely be the case) had no immigration to UK occurred for the past several decades, were this elasticity to be constant with respect to the number of immigrants, and even if such a claim were true the UK population would still reach 2.6 billion. If the rate of growth of the population itself impacted TFP negatively, then this provides an equilibrating mechanism to spread out the population growth over more years than above.

This model retains a number of key shortcomings. In particular, the lack of inclusion of any effects on total factor productivity on the origin countries from the migration of the majority of their population may bias the model’s results, while the lack of any convergence mechanism for countries with currently lower productivity means that the model may have overestimated immigration due to the potential for currently low-income countries to grow wealthy before their population entirely migrates. Additionally, this model is incapable of providing estimates for the change in aggregate global welfare and utility due to not containing any estimate of the effects on innovation or fertility from the policy, with such estimates of changes for native and global per capita income likely being the most relevant output. These limitations will be rectified in a future post.