Paying For Peace

How much would Russian soldiers need to be paid to defect if offered EU citizenship?

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has caused the loss of countless lives, hundreds of billions in damage and about $150bn financial and military aid from allies, primarily the United States and the Europe Union (EU).

One potential idea to end the conflict is to pay Russian soldiers, often unwilling combatants, to surrender. Indeed, the Ukrainian government, shortly after the invasion began, offered Russian soldiers 5 million roubles ($48,000), or four years' salary for the average Russian, to do so.

More than a year later, the scheme has received very little public attention. At the time, Bryan Caplan, an economist at George Mason University, said the scheme would have limited effect because Russian soldiers considering it had to weigh it against three large costs, namely the risks of:

Being shot for desertion by the Russian army

Ukrainian soldiers disobeying international law and shooting any captured prisoners

Them being returned to Russia in a peace deal where they would most likely face death or imprisonment for defecting.1

Caplan suggests an improvement: offering not only payment but also EU citizenship for Russian soldiers and their families. This means that defecting soldiers and their families can both establish themselves and permanently enjoy an income several times higher than their previous life while facing little risk of forced repatriation. Although this scheme has attracted some interest elsewhere, no attempt has yet been made to model its impact.

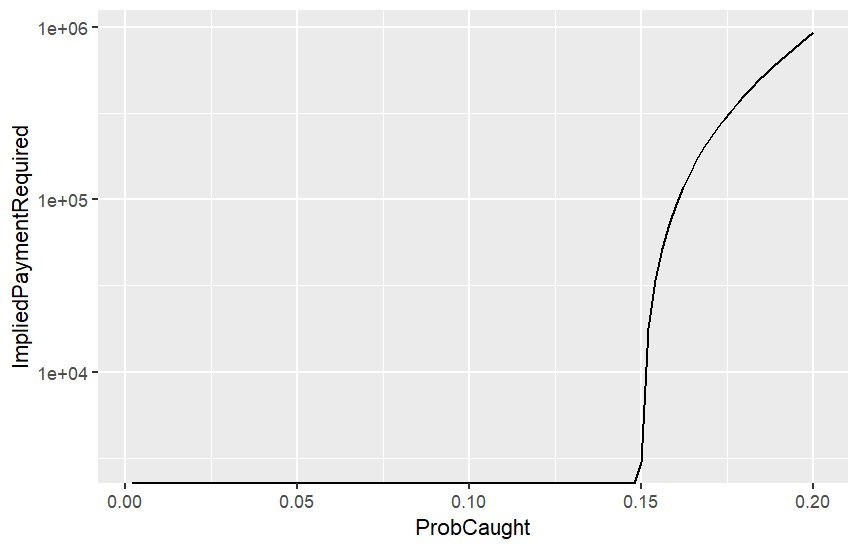

In this post, we provide a simple model of the effect of such a policy. Conservatively, we conclude that if there is a <17% chance of death while trying to defect, a $100,000 payment is sufficient to incentivise the average Russian soldier to do so – meaning that it might cost as little as $20bn to end the war entirely.

The Model

We’ll assume a rational choice model for any individual soldier. Therefore, if they receive greater utility from defecting than they do continue to fight, they will do so.

We first compute how much utility soldiers get from continuing to fight. We do this by taking the amount they value living in Russia (after the war) and multiplying that by the probability they survive the war, should they continue fighting, added to a constant term to account for whether they believe in the cause they are fighting for.2 See the equation below.

Then, we compute how much utility soldiers gain from defecting. We adapt the same model, adding a lump-sum payment, adjusting for EU incomes and replacing the probability of death by the probability of being killed during defection and the belief term with the utility cost of moving to a new country to live. See the equation below:3

Parameter Estimation

We now estimate the relevant parameters. We'll start with some key values:

Yhome: The per capita income in Russia is $32,862.60. Yforeign: Meanwhile, the highest per capita income (PPP) value in the EU is Luxembourg's at $115,683.49. Since Russians could choose any EU member state, selecting any other country means that they derive a strict increase in utility from their choice, rendering this a lower bound.

r: Based on the research by Matousek, Havranek, and Irsova 2019, the corrected discount rate is found to be between 0.15 and 0.33. We'll use the geometric mean, which gives us a value for 1-r of 0.76.

alpha: The current birth rate per capita in Russia is 0.75, and the alpha value for a steady-state population is 0.09, from Alexandrie and Eden forthcoming.

ghome: PWC predicts global economic growth at 2.7% per year for this decade. We'll assume Russia's growth (ghome) equals this, as its GDP per capita is around the world average. gforeignMeanwhile, average EU growth during the 2010s was 1.58%, which we'll use for the foreign growth rate (gforeign).

In terms of the war-related parameters:

D: Over the past year, Russia has seen around 50,000 deaths in the war from more than 750,000 deployed soldiers. Assuming the war lasts for another 2 years, we'll use a conservative death rate estimate (D) of 0.2.

H: The risks that Ukrainian soldiers shoot those attempting to surrender are rendered minimal by providing financial rewards to Ukrainian soldiers for capturing Russian soldiers.

B: We can estimate the utility of joining the military (B) by examining the large salary increases for potential Russian recruits in mid-2022 and the actual number of soldiers recruited. Despite significant financial incentives (up to 10 times regular military salaries) and reduced wages in other sectors, military recruitment declined after the war began. By comparing the current utility without B assuming a 3-fold increase in wages (41.4 utils) to the utility before B (46.4 utils), we conservatively estimate B at 5.0 utils.4

gamma: Based on a forthcoming study by McClements and Cheang, the cost of relocating is bounded by $62,000 for individuals with slightly above-average global income. This translates to 1.82 utils if consumed immediately, or more if consumed optimally, which it will be here.

The Results

Even if the probability of successfully surrendering appears high at 80% with a $1,000,000 payment, it's important to consider that soldiers can choose the timing of their surrender. With many opportunities to surrender, they can perform better than randomly sampling across these chances would suggest.

At a more reasonable payment of $100,000, a combined value of 0.17 for the cost of human lives and the difficulty of surrender (H+T) would be sufficient. This scenario becomes more plausible if the Ukrainian army adapts to make surrendering as easy as possible for Russian soldiers. If all but 200,000 soldiers were to defect under these conditions, the Russian war effort north of Crimea could be all but defeated, costing only $20bn. This is a relatively small price compared to the $150 billion spent on the war so far, with no end in sight.

Estimating The Impact

To estimate the potential gains of the scheme implemented successfully, we can use a modified version of Lancaster's Laws, as presented in Taylor 1981, a set of mathematical models used to describe the relationships between various factors in war, such as force size, attrition rates, and the duration of a conflict.

As there is currently insufficient or unreliable data on army sizes over time or casualty figures for individual battles, we make the following assumptions for the purposes of calculating a ballpark guess:

Wounded soldiers are permanently taken out of action.

The Russian army has a constant strength of 500,000, while the Ukrainian army has 700,000 soldiers.

Both armies maintained these numbers throughout the war.

Russia has suffered 200,000 casualties (dead and wounded) to date, while Ukraine has experienced 120,000 casualties.

Russia or Ukraine would each surrender if they suffer over 50% of their current strength as casualties.

Feeding these into a model produces the following results.

Even if there were only several hundred defecting a day, these results imply the war could be shortened by over a year, saving many billions of dollars and tens of thousands of Ukrainian lives.

Possible Variations

If actually implemented, policymakers might want to consider a number of variations to the policy to make this more effective, such as:

Pay higher-ranked or better-trained Russian soldiers more to defect, and to bring their subordinates with them,

Paying Russian soldiers for bringing equipment with them,

Pay Ukrainian soldiers for prisoners they captured to ensure the Hague Conventions are obeyed,

As Caplan initially proposed, offering a higher initial payment to soldiers who initially defect incentivises faster adoption and increases the credibility of the scheme.

Discussion and Conclusion

In the worst case, even if Russia manages to significantly increase surveillance on its troops, maintaining desertion at current levels and closing its borders to prevent the families of defecting soldiers from leaving under the scheme. Despite these countermeasures, both actions would come at a high cost for Russia. Increased surveillance would likely further diminish the already low morale among soldiers while closing the borders would destabilize the existing regime and increase trade costs.

Furthermore, it might at first seem morally unjust that attacking Russian soldiers would be offered EU citizenship when this is not available to Ukrainian soldiers defending their homes. We hope that, if this scheme is implemented, the expedited end of the war opens the door for Ukrainian EU membership, affording all Ukrainians such a right.

Considering these factors, this scheme represents a highly cost-effective way to gain an advantage in the war if it works as intended. Even in the worst-case scenario, the strategy could still yield considerable benefits without incurring any costs beyond the paper on which the announcement was written.

Eg. Operation Keelhaul.

We also consider the effect of intergenerational altruism, as citizenship is heritable.

For simplicity the lump-sum payment is presented as consumed within a single year: the results section assumes the payment is actually consumed so as to maximise welfare.

The 16% probability of a Russia-NATO war by 2050 was predicted by Metaculus users at the beginning of 2022. This analysis assumes the probability doubled uniformly over the period, Russian civilians have a zero probability of death in such a war, and Russia's casualties are proportional to those currently experienced in Ukraine. These assumptions result in a conservative D value before the war of 0.0024.

Some unaddressed problems:

1. What about the negative effects on the Ukrainian military? It seems like Ukrainian soldiers are making $40k or less. Some might rationally support the plan in order to bring an end to the war, but many would be bitter if their government paid 2.5xtheir annual salary to the enemy. The impact could outweigh the benefit.

1A. Paying bounties to Ukrainians might help the problem above, but could also create a discipline problem on the battlefield with capturing being incentivized over other activities.

2. What about war criminals? Can they defect? If defectors are arrested instead of rewarded that can’t get out or the program won’t work. If war criminals can defect, it might double down on the problem above.

2A. What about mercenaries and the Ukrainian citizens of the occupied territories fighting for Russia? For the former, they might be militarily useless, but Russia would have an awesome recruiting tool to drain money from the EU/Ukraine. For the latter, Ukraine might balk at paying collaborators.

2B. What about the regular criminals fighting for Wagner? Will the EU want to offer cash and citizenship to some rapists and murderers?

And an alternative formulation: what about EU/US temporary work visas with a path to citizenship for military age Russian men (plus immediate family) who can make it out of Russia to present themselves. This drains the manpower pool for the military and economy, forces Russia to overtly prevent citizens from leaving, and sidesteps problem 1, and maybe problem 2.

Using per capita PPP GDP doesn't make too much sense. Better would be median income at PPP.

It is another question whether the resettled Russians could make it to the median income level, and surely that is not independent of destination country, but that is a harder fix. Still, I might attempt to add a parameter accounting for that and then estimate a value.